Square Theory

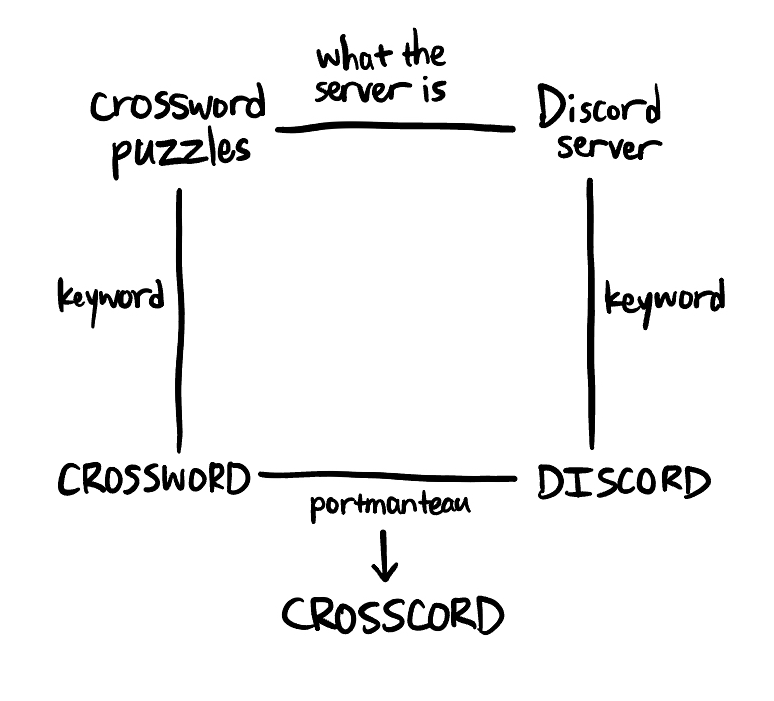

The story starts in Crosscord, the crossword Discord server. Over 5,000 users strong, the server has emerged as a central hub for the online crossword community, a buzzing, sometimes overwhelming, sometimes delightful town square where total noobs, veteran constructors, and champion solvers alike come together to talk about words that cross each other.

Square roots

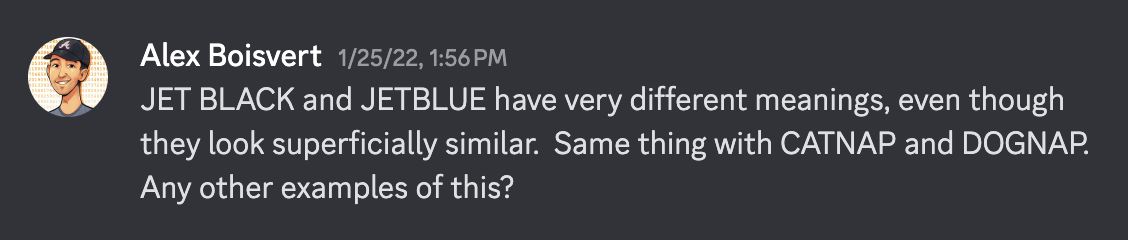

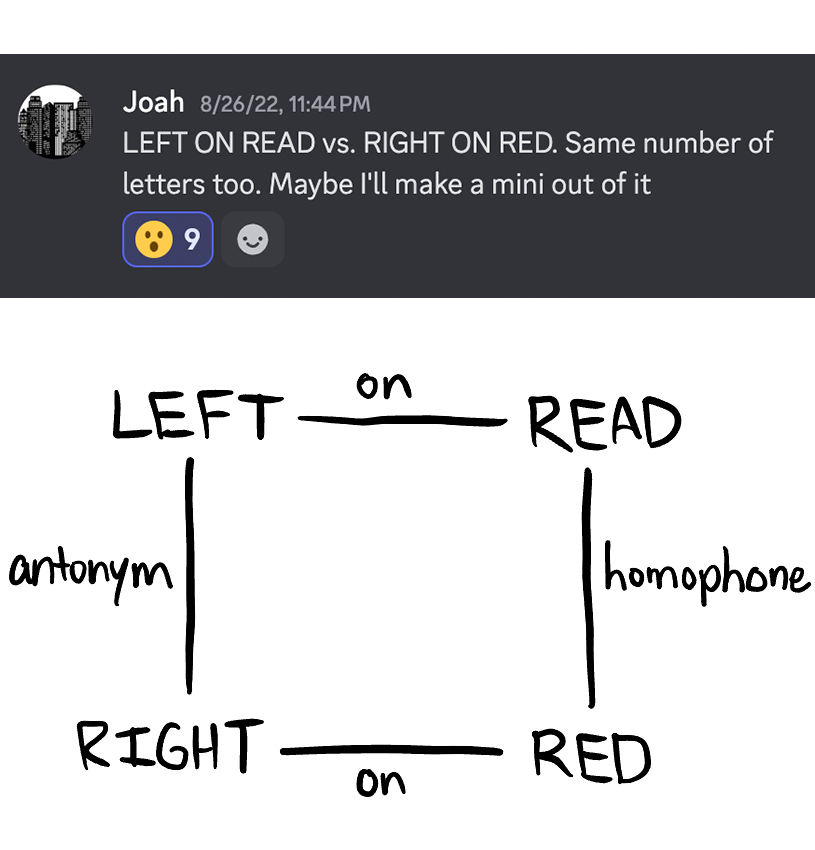

We direct our attention toward the #etuiposting channel, Crosscord’s designated space for shitposting (so named because ETUI, a sewing case, is a prototypically shitty piece of crosswordese). There, one afternoon in January 2022, crossword constructor and Crossword Nexus warden Alex Boisvert posted what seemed at the time to be an innocuous, mildly interesting observation:

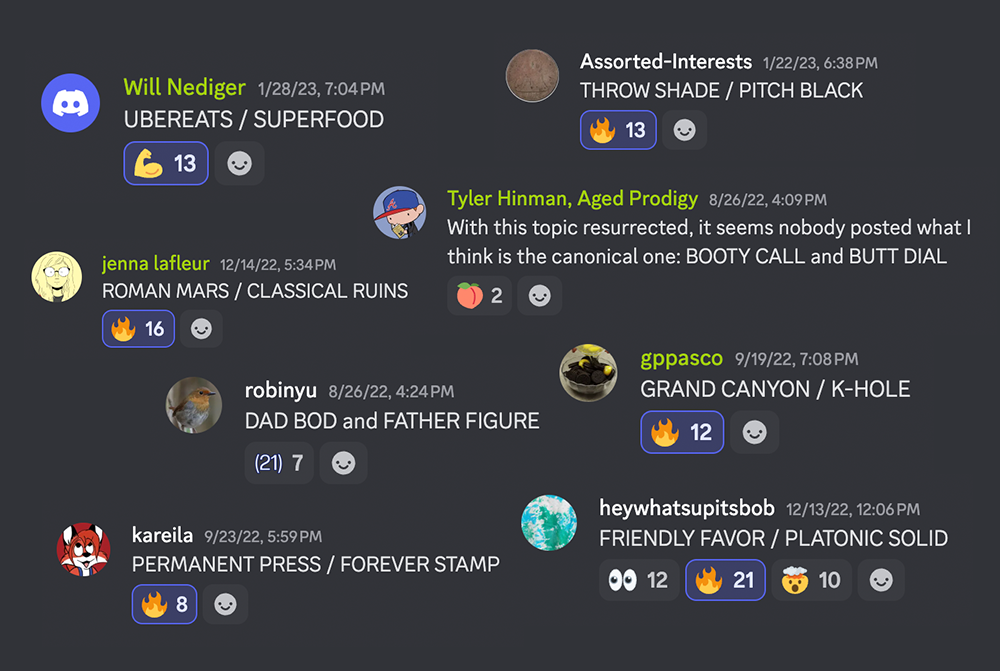

Suffice to say, the Crosscord hivemind had other examples of this. Will Nediger replied a few minutes later with the clever MULTITOOL and MULTIPLIERS (words with completely unrelated meanings, despite the fact that PLIERS are a TOOL). Several messages later, Alex chimed back in with the elegant PUB QUIZ and BAR EXAM, a pairing that had been used in some form in crosswords by constructors Christopher Adams (2018) and Robyn Weintraub (2021).

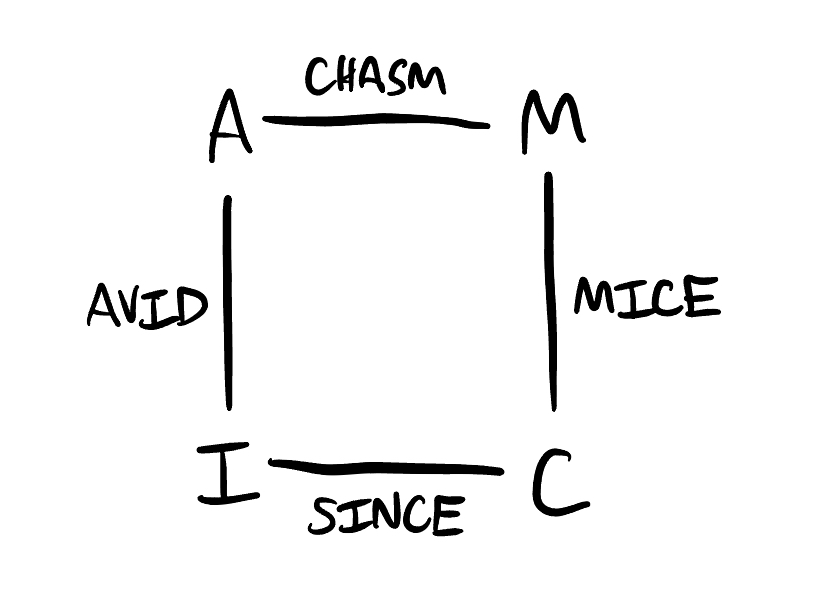

Something about this concept—two sets of synonyms (PUB and BAR, QUIZ and EXAM), which when paired together, form phrases that themselves are not synonyms (PUB QUIZ and BAR EXAM)—captured the minds of Crosscord. Suddenly, the floodgates were open.

Intermittently over the next year, #etuiposting would be flooded with these pairs of pairs. They became too much even for the shitposting channel, and were ultimately confined to a thread called #double-doubles (a name Bob Weisz and I both proposed simultaneously). Today, more than three years after Alex’s original prompt, the thread still remains active, a wordplay oasis of over 3,000 posts.

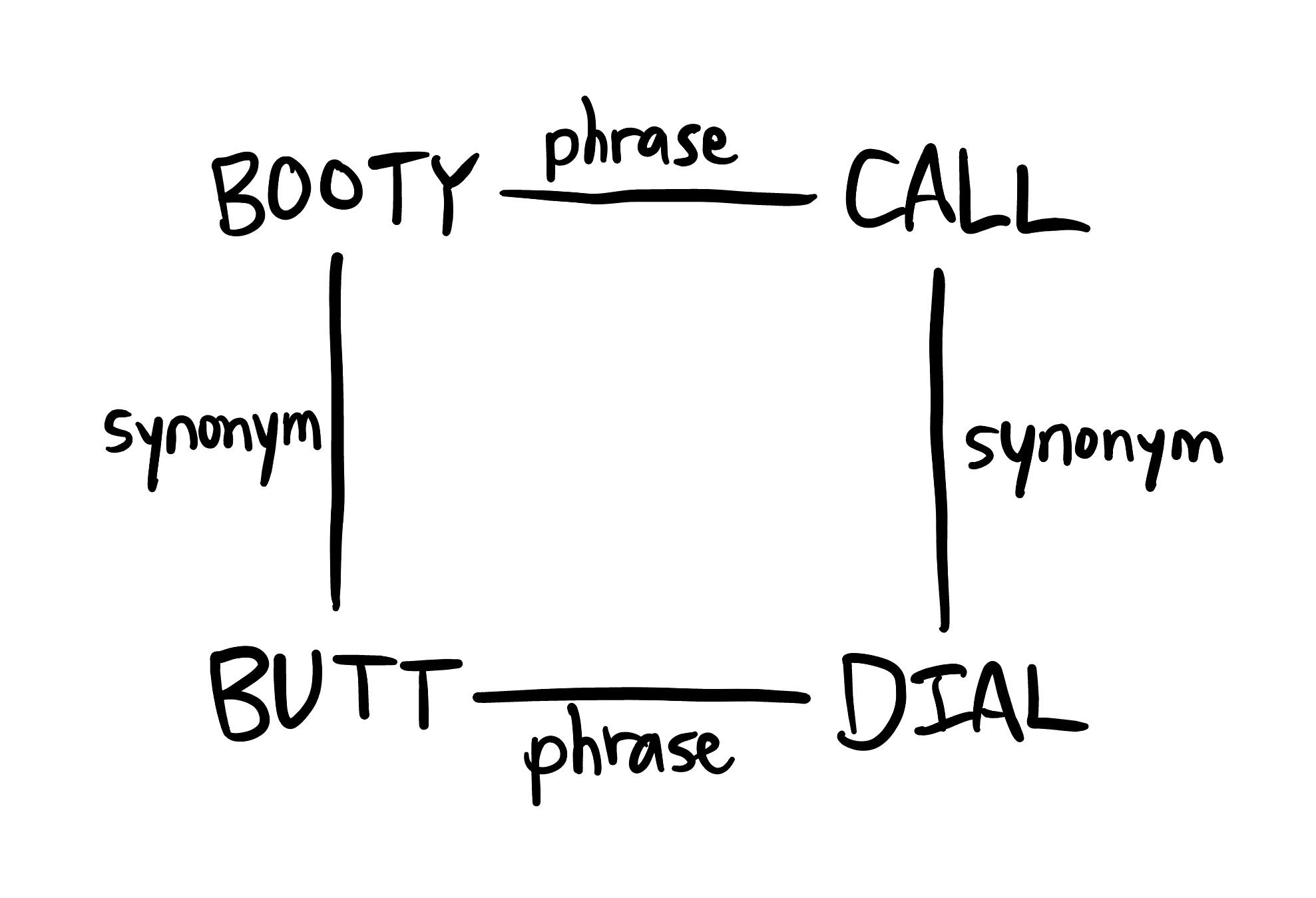

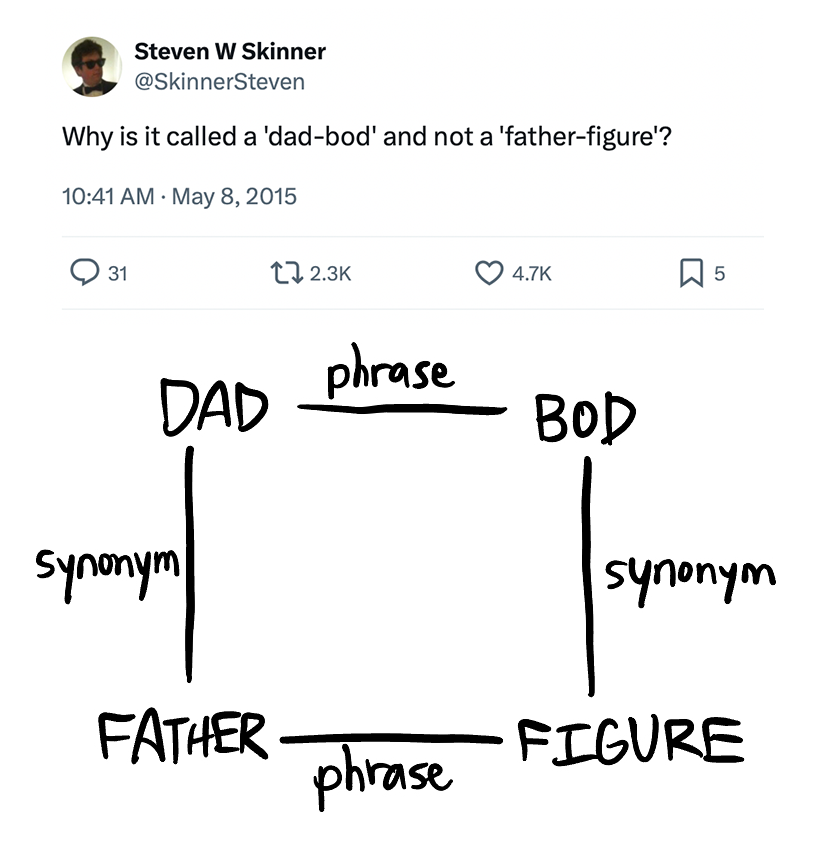

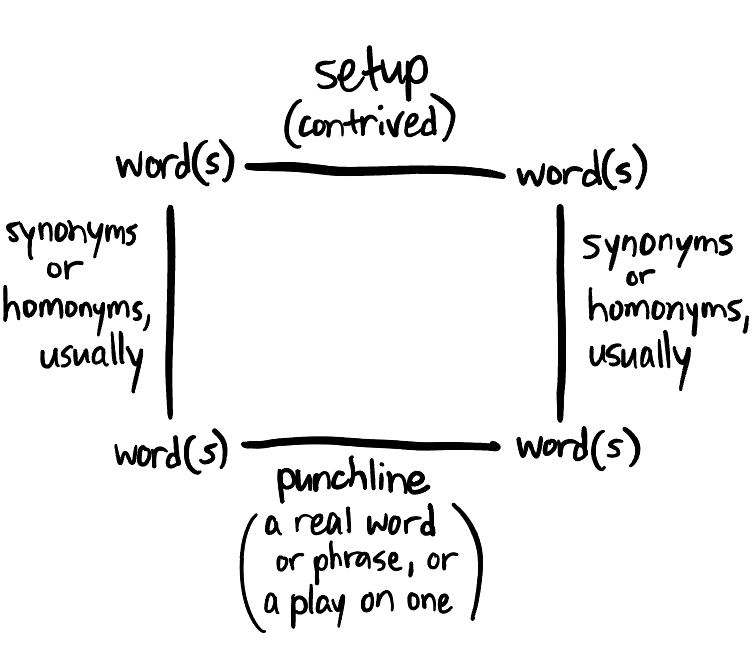

There’s something going on here. Something more than a shitpost or an ephemeral trend. Double doubles have the proverbial juice, and the juice lies in their structure. Each pair of pairs can be modeled as a square, where the corners are words and the sides are relations between those words:

It’s this square structure that makes each double double feel tight, feel satisfying, feel like a real “find”. This is the essence of what I’ve started calling square theory, and it applies to much more than just posts in a Discord server.

Just like it’s satisfying when an essay or a news story comes full circle, or mindblowing when you find an unexpected cycle in your network of friends, it’s inherently compelling when things wrap around and complete the square. Let’s break it down.

The theory of everything

Crosscord wasn’t the first to catch onto this kind of formation: Ricki Heicklen has maintained a huge list of double doubles (which she calls “Unparalleled Misalignments”—itself a sort of double double) since 2018, and the success of her recent Twitter thread about them is another testament to their widespread appeal. Pairs of the same form pop up on a regular basis in the form of crossword clues and Twitter jokes:

![Crossword clue [Top gun?] for TSHIRTCANNON, with a square showing TOP - phrase - GUN connected via synonyms to TSHIRT - phrase CANNON](/assets/images/square-top-gun.png)

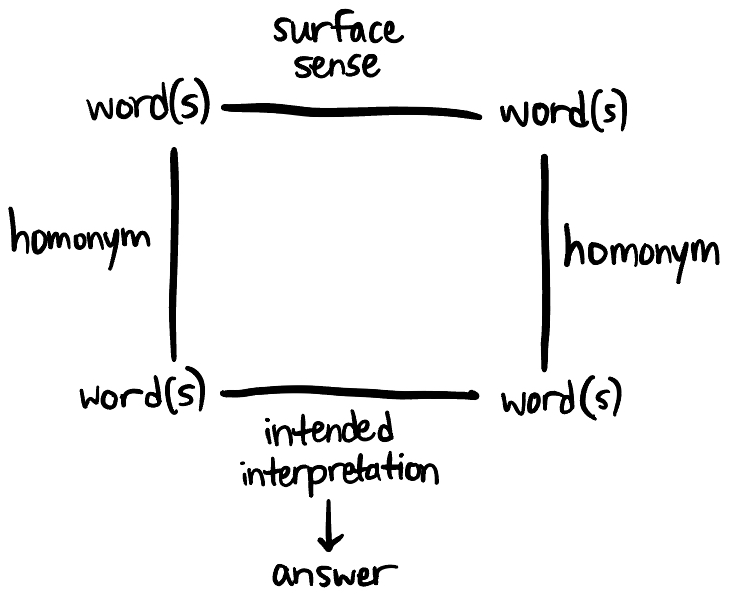

However, there’s nothing about the square structure that dictates the edges must represent phrases and synonyms. Each edge of the square can be any relation that connects its vertices (but generally, the stronger the relations, the stronger the square). The vertices don’t even necessarily have to be words—they can be any entity or concept.

It evokes the mathematical field of category theory, which very abstractly studies mathematical objects and the relations between them. It’s the topology of the square that makes it satisfying, regardless of what the edges and vertices represent.

Members of the #double-doubles thread have already noticed this, consciously or not, with many of the posts interpreting the original prompt more liberally and swapping out the “synonym” relation for something else:

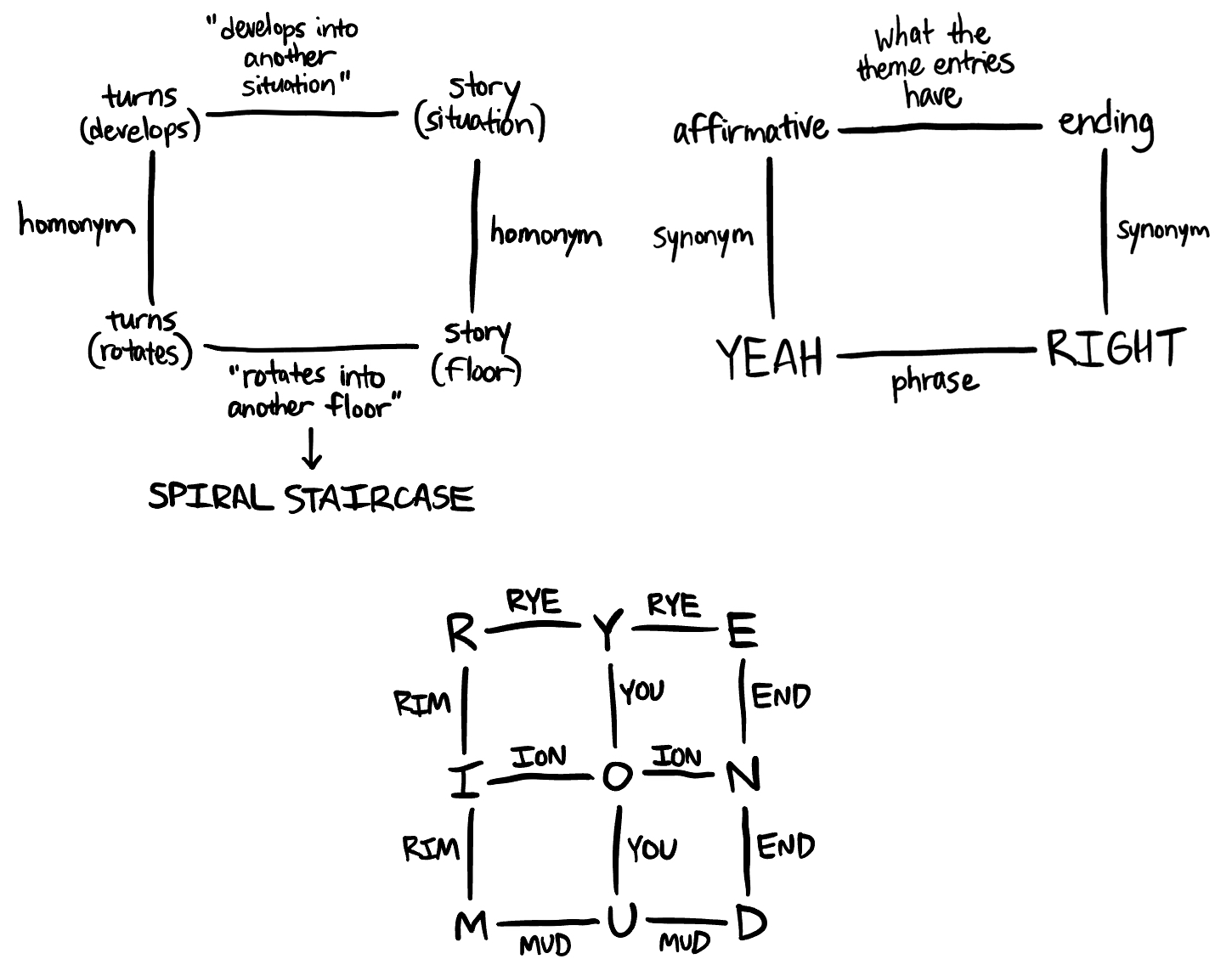

Sometimes it feels like the #double-doubles thread has devolved into just #question-mark-clues (crossword clues that are trying to trick you, requiring you to reinterpret them beyond their words’ most likely meaning, or “surface sense”). But that’s no coincidence—abstractly, every question mark clue takes the form of a square.

When brainstorming for question mark clues, crossword constructors experience this on a regular basis. You start with the answer at hand, playing word association with it in search of a combination of words that usually means one thing (the surface sense) but can be interpreted differently (the intended interpretation) to point to the answer, thus completing the square:

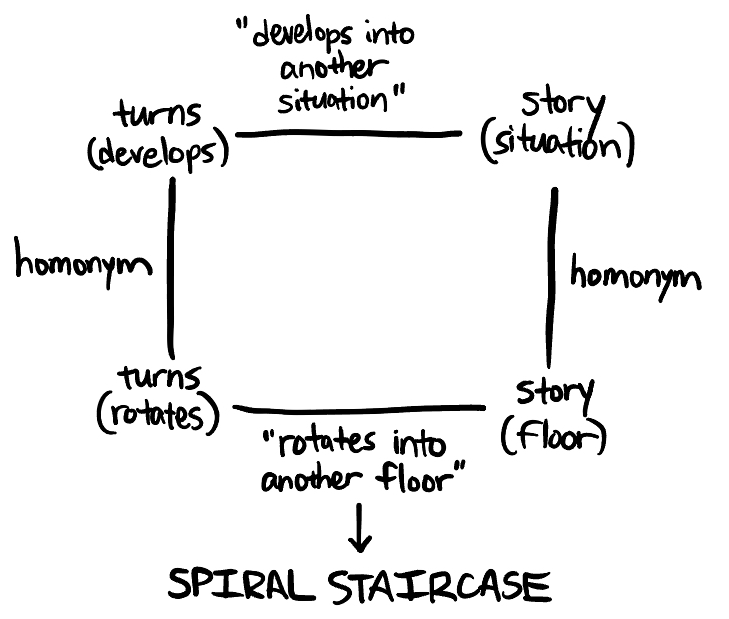

Take Will Shortz’s all-time favorite clue for instance, from a 1995 Martin Ashwood-Smith puzzle: [It turns into a different story] (which deviously didn’t even include the question mark). On the surface, “turns into a different story” typically means something like “develops into another situation.” But the intended interpretation takes the clue’s words to mean “rotates into another floor,” leading to the correct answer of SPIRAL STAIRCASE:

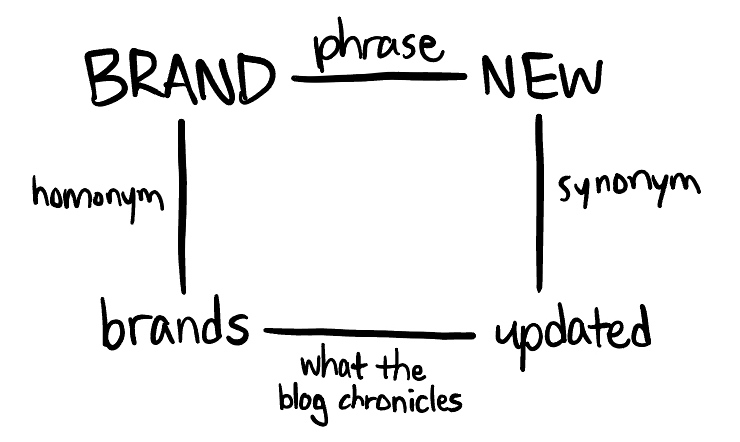

You might be familiar with this same sort of brainstorming if you’ve ever tried to come up with a clever title for a research paper, or an apt name for a company. There are plenty of names that might make you go “I guess that could work,” but it’s the square-completing ones that make you go “that’s the one,” or “that’s so good!”

One of my favorite examples of this is Brand New, the blog that catalogues the latest in corporate rebrands. Leave it to a branding blog to have a name this immaculate:

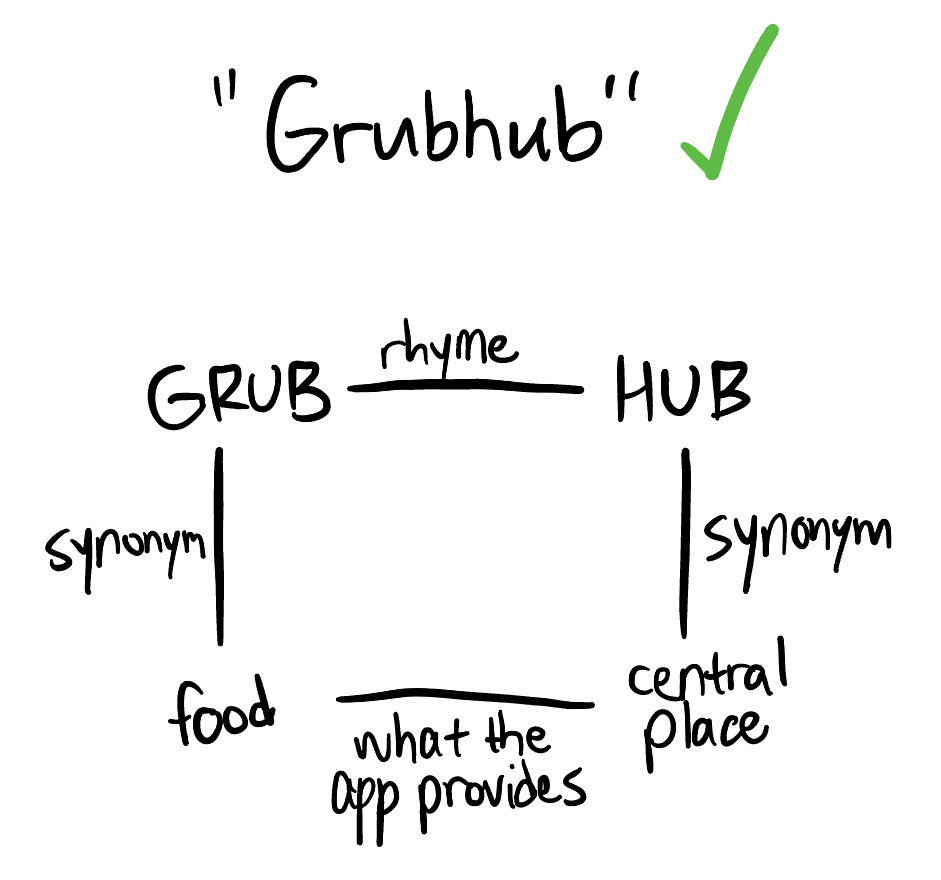

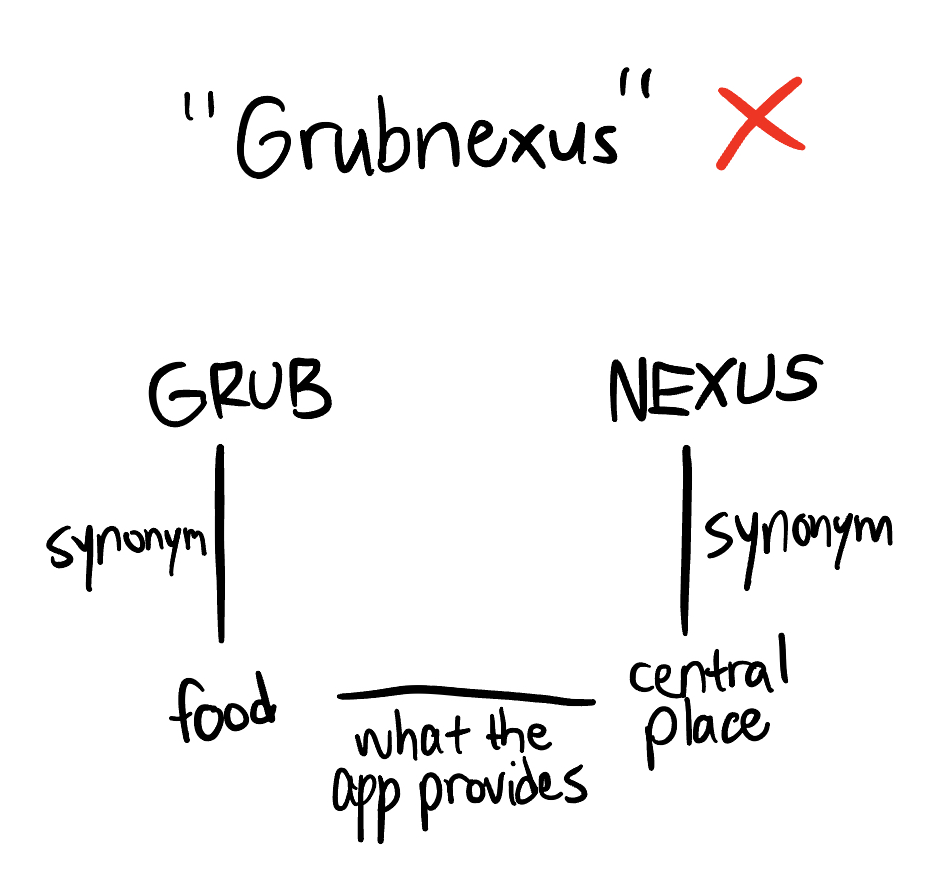

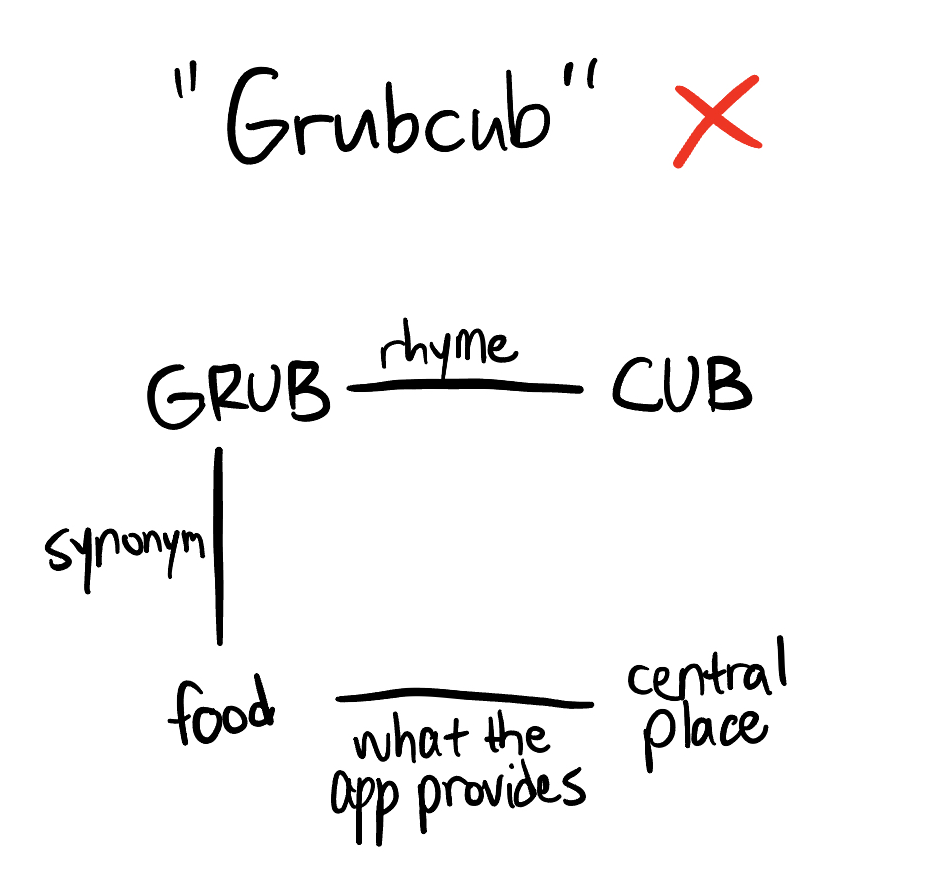

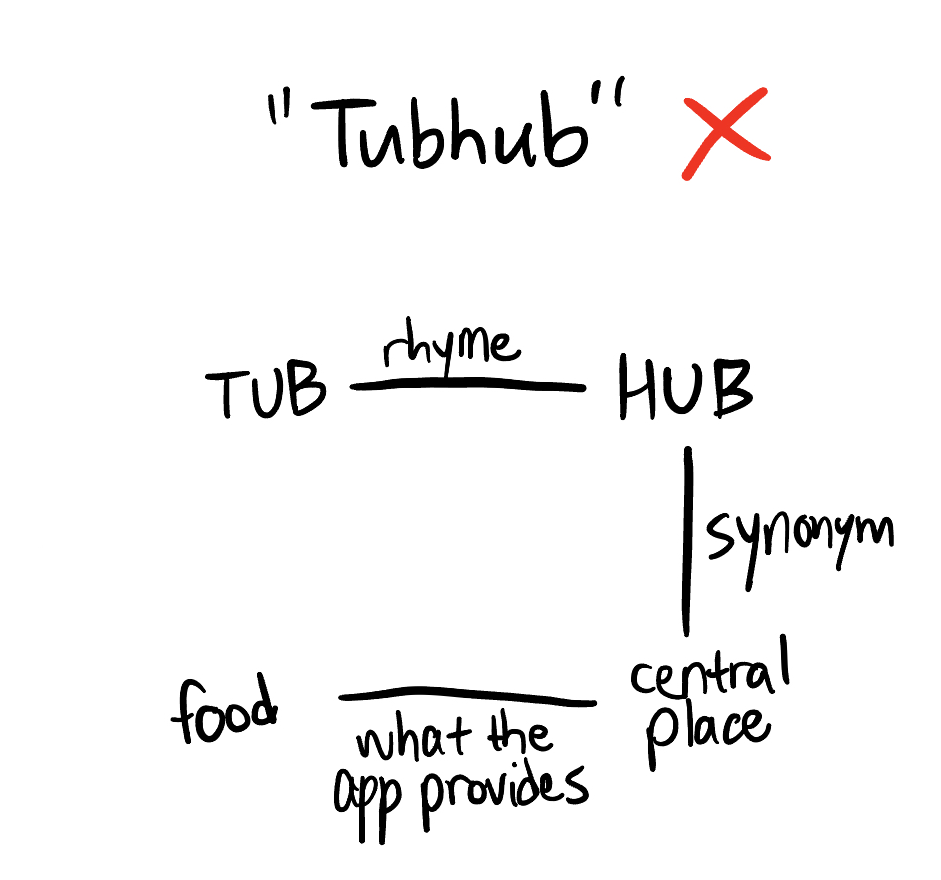

Even a seemingly straightforward brand name like Grubhub can exemplify the power of square theory. Presumably, Grubhub’s branding team started with a concept (a centralized app for food deliveries) and came up with a name that completes the square. But remove any edge of the square (besides the edge that dictates the app’s purpose), and you’re left with a name that only kinda works:

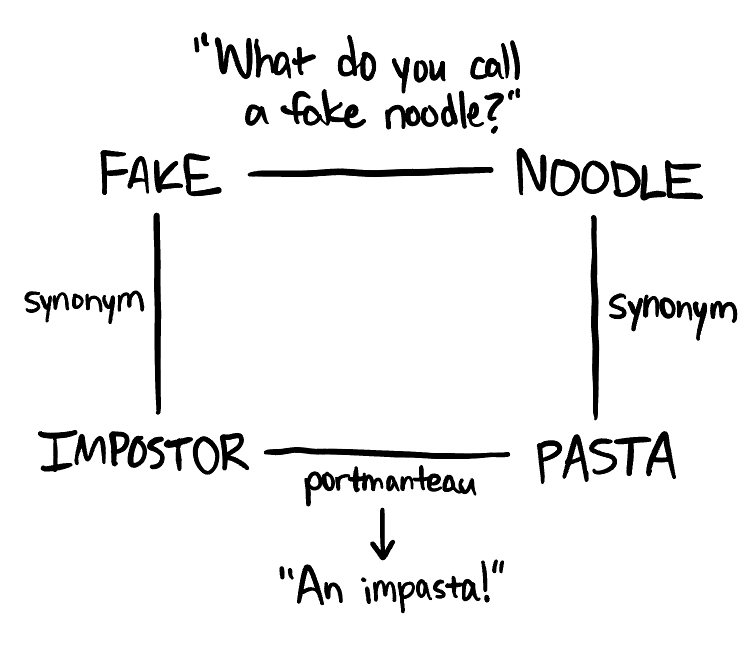

Aside from crossword clues and brand names, squares appear in the wild all the time in the form of jokes. There’s a vast universe of pun-based jokes (often in the form of dad jokes, or Twitter jokes, or Punderdome puns) that can be modeled as a square, where one side of the square is the contrived setup (“what do you call an X with a Y?”) that connects in at least two ways to the punchline (“an algebra problem!”) on the opposite side.

The strength of the joke rests in the strength of the setup, the punchline, and the connections between them—and if every side of the square is strong, you might have created something funny:

Getting into shape

You might be thinking: what’s so special about a square? What about triangle theory, or pentagon theory? (Or rectangle theory? Or rhombus theory? Okay, side lengths and angles don’t matter here.)

Well, it’s true that there’s something compelling about any loop-closing property, regardless of side count—a story that comes full circle is still satisfying no matter how many points it hits in between, and it’s still neat to discover a triangle of people who coincidentally know each other.

But here’s what I think makes squares special: a square is the simplest polygon that has non-adjacent sides. In a triangle, each side is adjacent to the other two sides. But in a square, opposite sides have no points in common, which makes any connection between them feel surprising, like a coincidence. In pentagons and beyond, this still holds, but the extra sides add complexity that make them feel slightly less elegant. Nevertheless, other shapes can be interesting too, but I see them as the exception, not the rule.

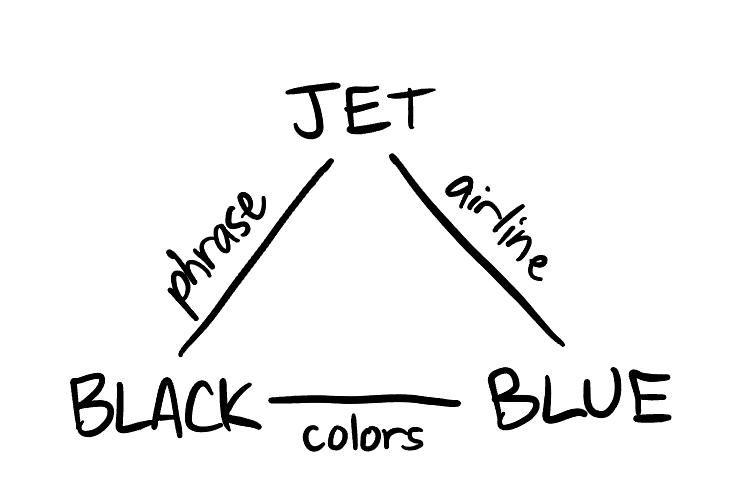

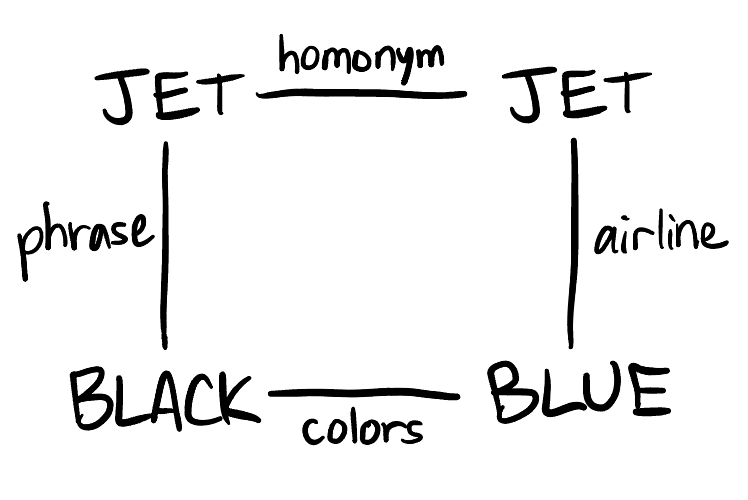

Remember Alex Boisvert’s original JET BLACK / JETBLUE example? Seems like it could be modeled as a triangle, right? Well, it turns out the “jet” in JET BLACK refers to the gemstone jet, which is etymologically unrelated to JETBLUE’s airplane jet, so it’s actually more properly modeled as a square:

Times square

Now that I’ve established that square theory applies to more than just crosswords, it’s time to talk about crosswords again.

It’s typical for American-style crosswords (à la New York Times) to have a theme, which will generally consist of the 4–6 longest Across entries in the grid, often including a “revealer” that ties the theme together. Nowadays, it’s common gospel among crossword constructors that themes should have some sort of wordplay-based connection—that is, a theme like “famous basketball players” or “brands of cereal” is unlikely to elicit a real “aha” moment from solvers, and thus unlikely to be accepted at major crossword outlets.

So what makes for a good crossword theme? Consistency is definitely key, and a notion of “tightness” is important too (the set of possible theme entries shouldn’t be too much bigger than the theme set that appears in the puzzle). But time and time again, I’ve noticed that what makes a theme really pop is—you guessed it—when it completes the square.

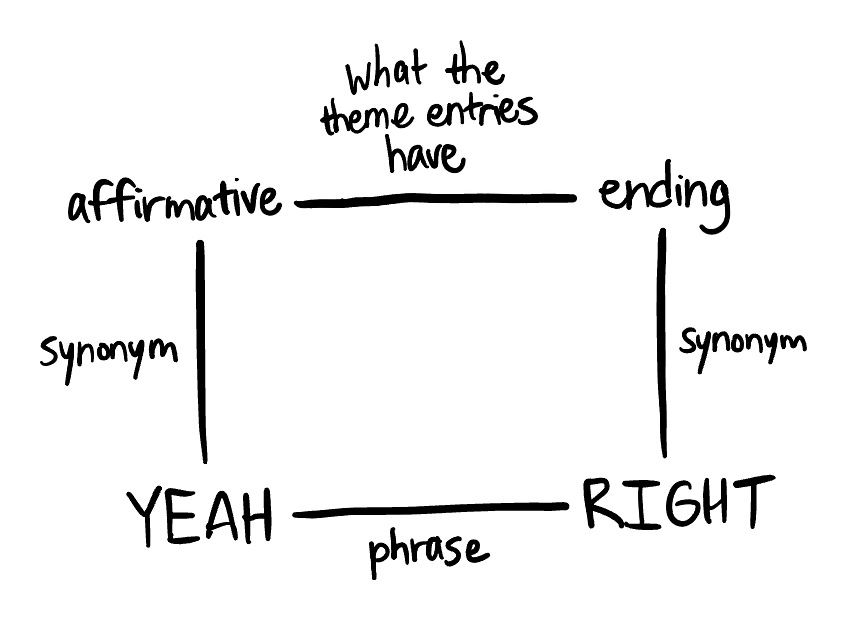

Take, for example, the Monday, February 17, 2025 New York Times crossword by Kate Hawkins and Erica Hsiung Wojcik, which features a great execution of a typical Monday theme type. In this puzzle, the seemingly unrelated theme entries SCRAPBOOK, POPEYES, UNDER PRESSURE, and GIDDY UP are united by the fact that they each end in an affirmative (OK, YES, SURE, YUP).

In a vacuum, this fact wouldn’t be that interesting, but Kate and Erica give the theme a raison d’etre with the revealer YEAH RIGHT, clued as [“Uh-huh, I bet” … or a literal description of what 17-, 24-, 36- and 50-Across all have]—that is, each themer has a synonym for “YEAH” on its “RIGHT” side. The key here is that YEAH RIGHT itself is an idiomatic phrase (meaning “Uh-huh, I bet”), and not just an arbitrary description of the theme mechanic, so it completes the square:

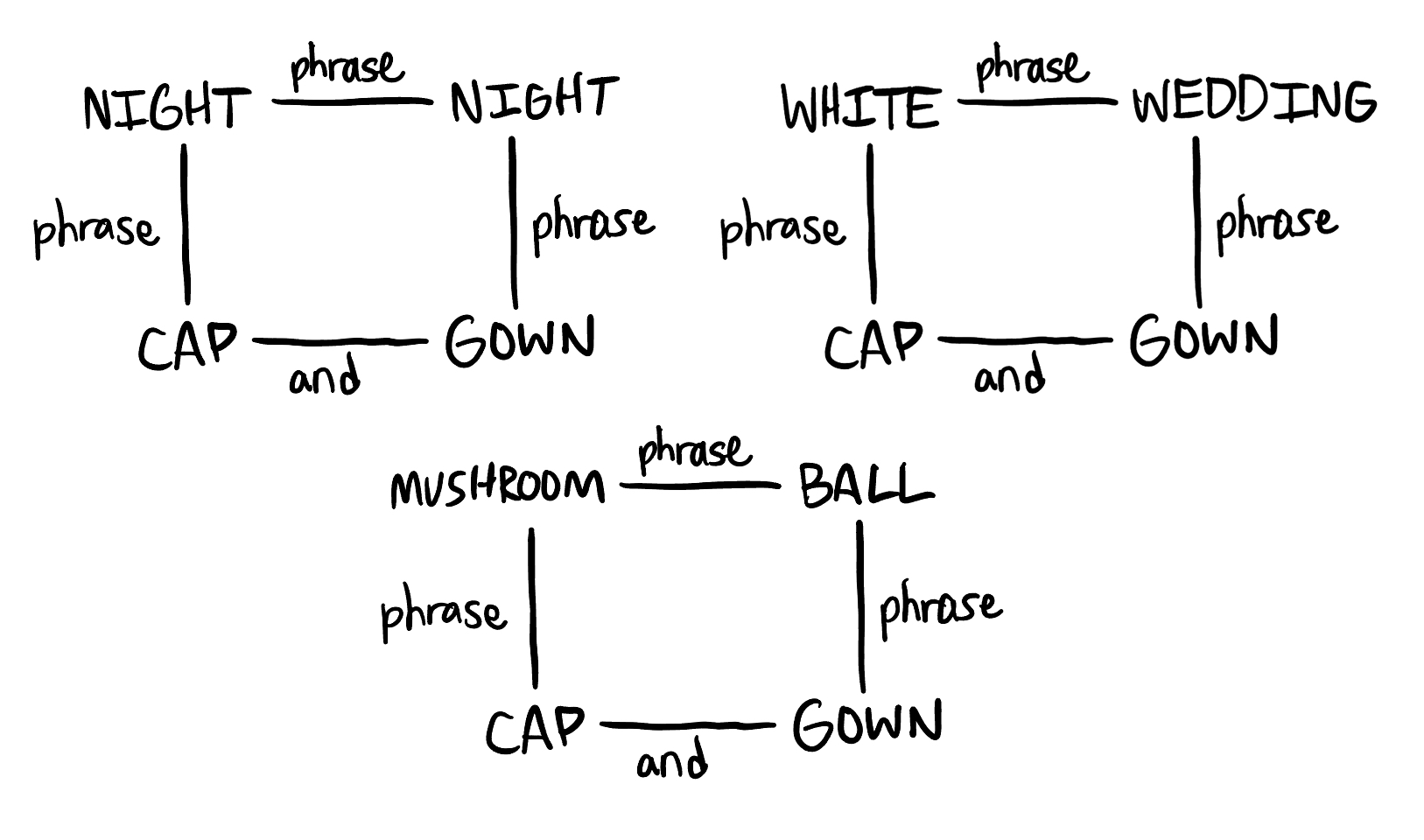

But it doesn’t stop there. Consider the Monday, February 18, 2019 New York Times crossword by Leslie Young and Andrea Carla Michaels. The theme entries here are NIGHT NIGHT, WHITE WEDDING, and MUSHROOM BALL (you know, like a vegetarian meatball), and the revealer, clued as [Graduation garb … or what the compound answers to 17-, 28- and 44-Across represent?], is CAP AND GOWN. That is, the first part of each themer can precede CAP (e.g. MUSHROOM CAP), and the second part can precede GOWN (e.g. BALL GOWN). This maps pretty squarely onto not one, but three squares, one for each theme entry:

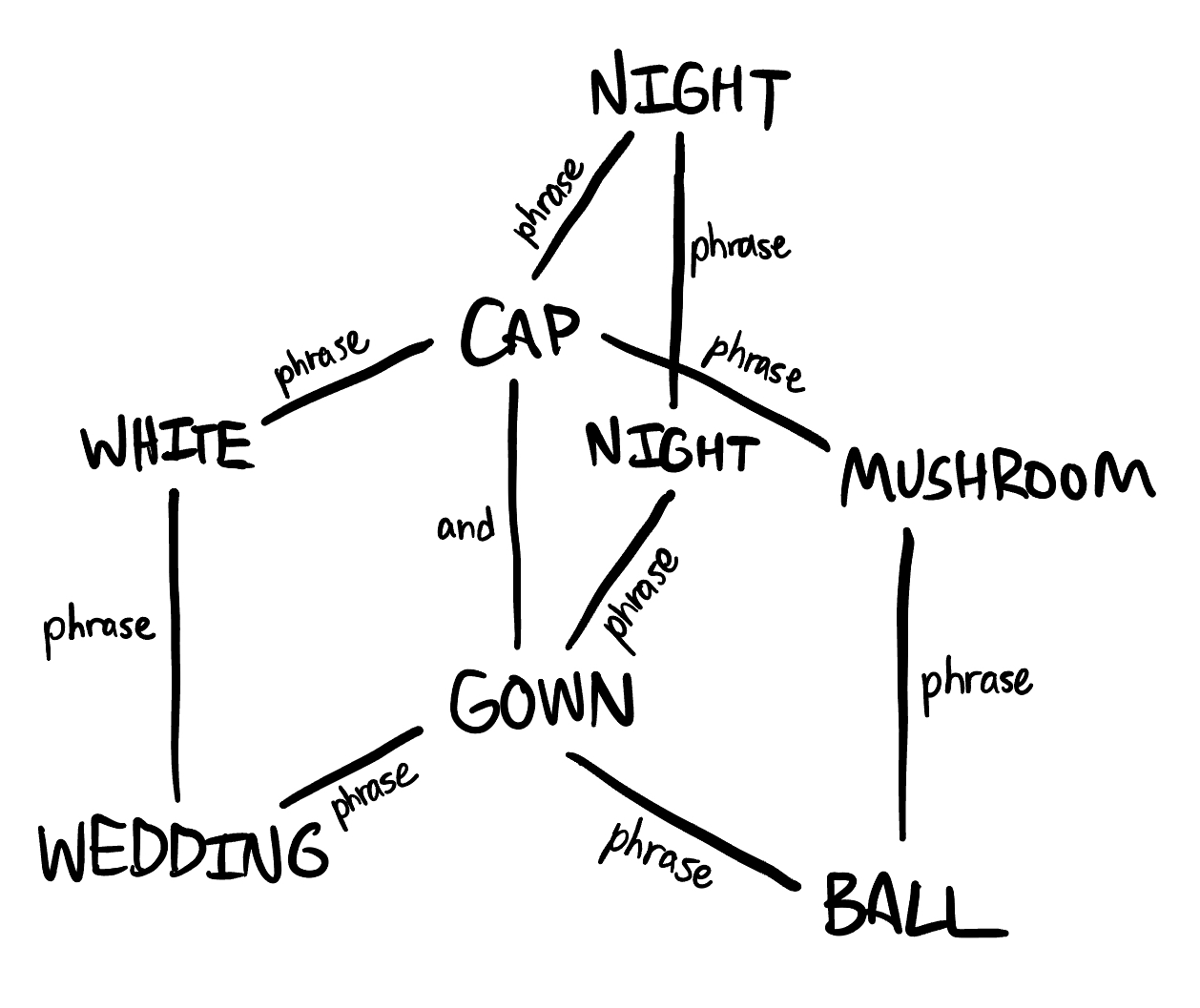

And just for fun, we can conjoin the three squares by their CAP AND GOWN edges to form a unified graph that represents the entire theme’s topology:

The final crossword we’ll look at, and maybe my favorite crossword of all time, is Alina Abidi’s Wednesday, August 18, 2021 New York Times crossword, with a theme that feels almost impossibly tight.

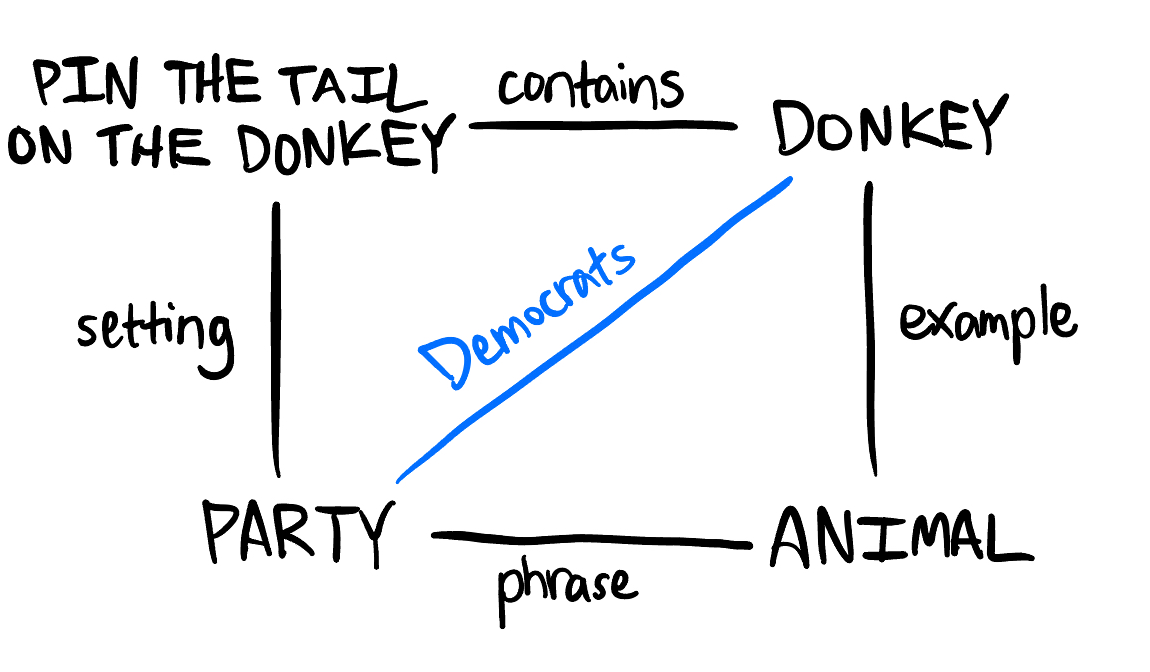

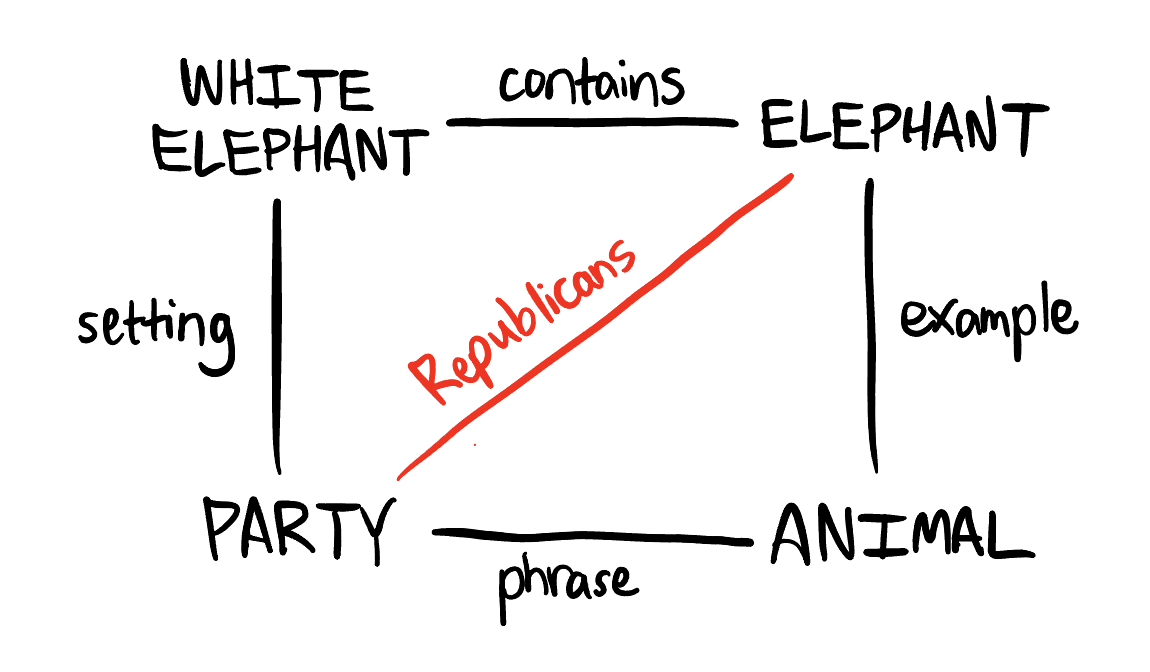

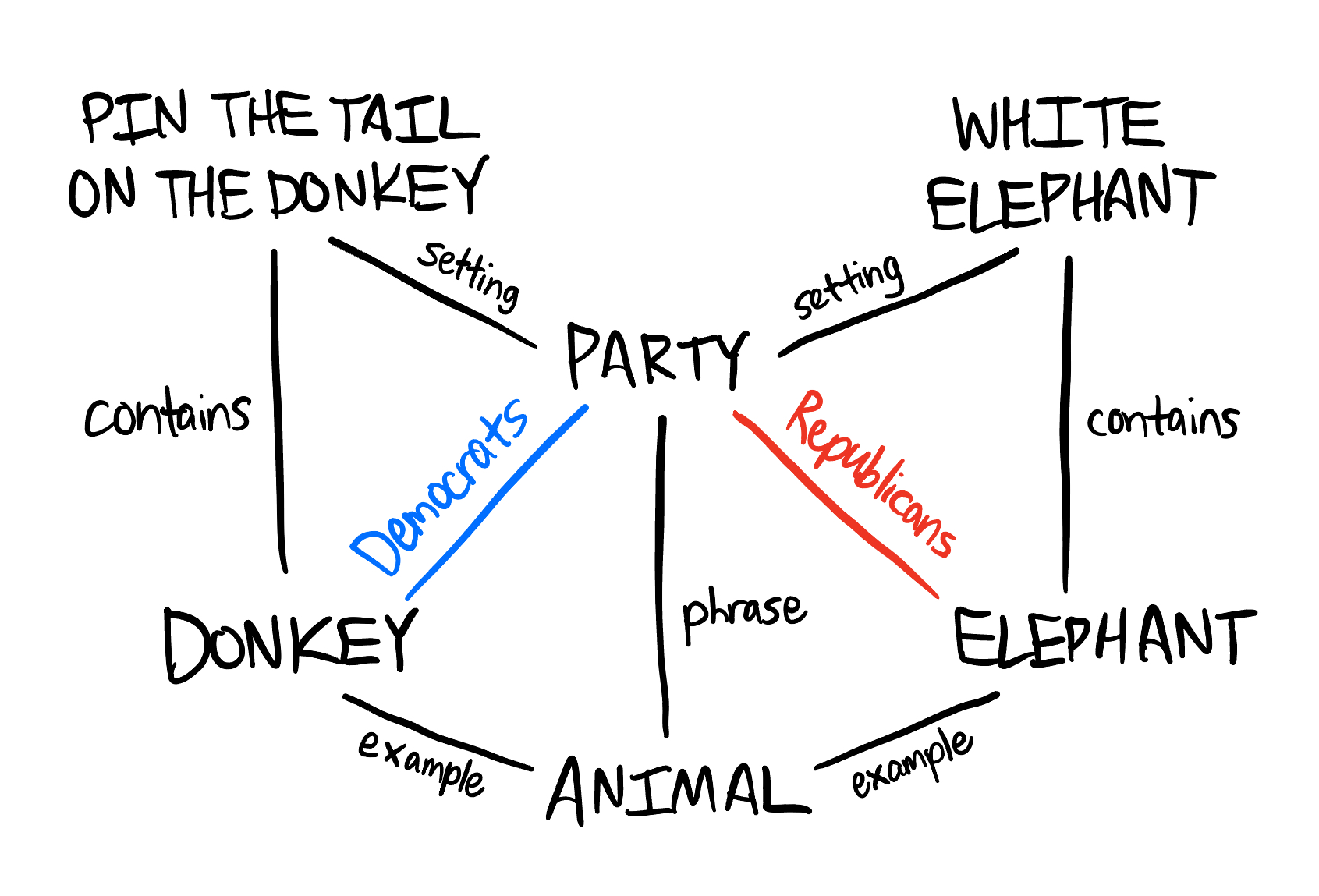

The puzzle has essentially two theme entries, PIN THE TAIL ON THE DONKEY and WHITE ELEPHANT, with the apt revealer PARTY ANIMAL [Frequent reveler, or a hint to 16-/26- and 36-Across]. That alone is clever, since both themers are party games with animals in their names. But then Alina hits you with the second revealer of THOMAS NAST [Cartoonist suggested by this puzzle’s theme], pointing to the fact that not only are the DONKEY and ELEPHANT animals in party games, but they are also the animals that symbolize the Democratic and Republican parties, as popularized by Thomas Nast’s political cartoons.

This is the kind of theme that really sticks with you. Or at least it stuck with me, and I tried for years to understand why it felt so amazing. And then I realized square theory offered an explanation. Squares, as we know, feel tight, satisfying, and clever. But Alina’s theme takes that one step further, creating for each theme entry a square with an extra diagonal through it, reflecting the connection between each animal and a political PARTY:

And again, we can combine these two super-squares into one unified theme graph:

Granted, there’s more to a crossword than the structure of its theme, and it can be reductive to distill it into a graph like this. Still, for many puzzles, square theory can serve as an illuminating proxy for the intricacy and tightness of a theme. But that’s not all it can do.

Letter box

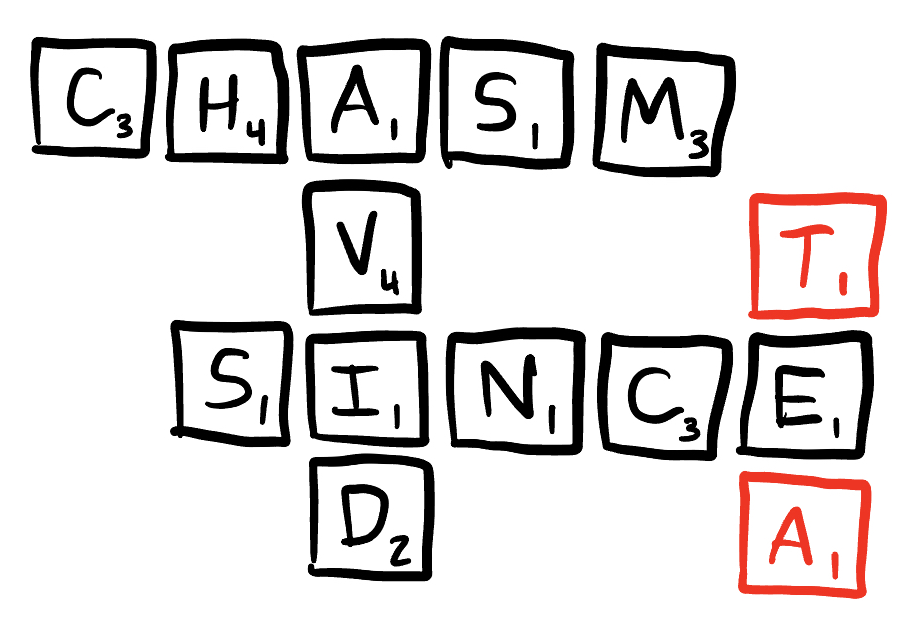

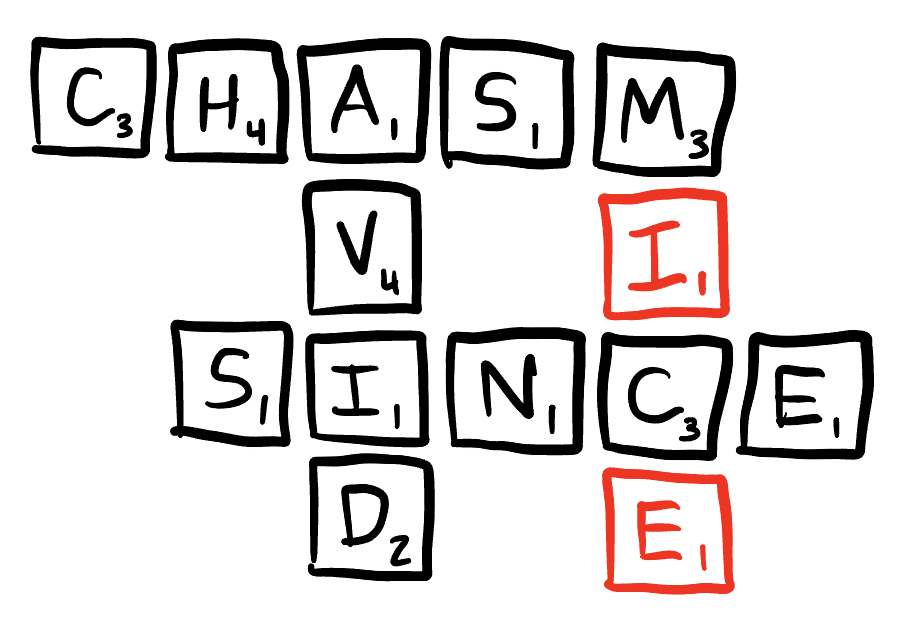

Let’s talk about Scrabble, one of the seven most important games out there. If you’ve ever played Scrabble (or similar games like Bananagrams), you’d know that every word you play has to intersect another word that’s already on the board.

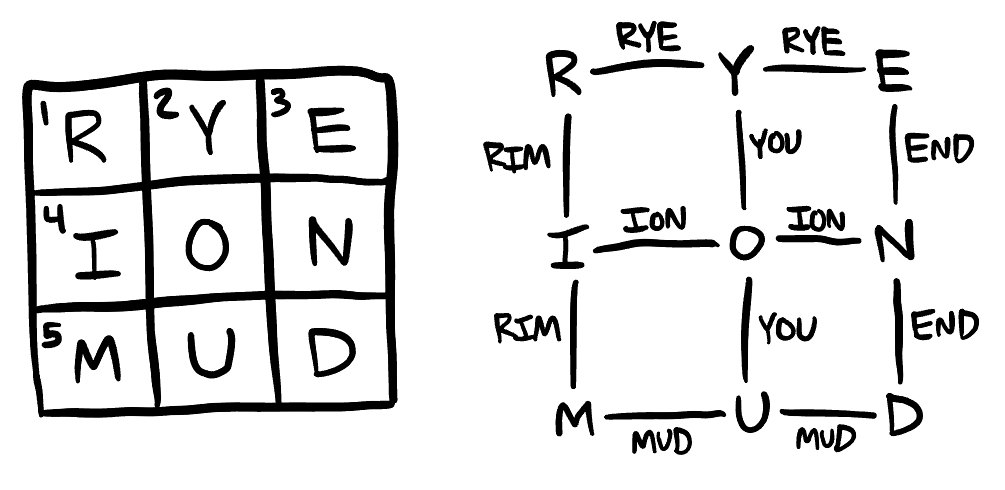

But occasionally, you’ll think up a play that validly intersects not one, but two words on the board, forming a rectangle of words. Plays like this have a certain panache. They’re satisfying, they make you think, “ooh, nice.” And of course, they can be modeled with square theory:

You might be thinking that the edge relation here (a word that contains both letters) feels a little flimsy, since not every letter in the word is used. But what if every letter in the word was used? What if we could have a dense network of interlocking squares, where every letter was part of exactly two words? Well, we can, and it’s called an American-style crossword.

In American-style crosswords, every letter is mandatorily “checked” (part of an Across and a Down word), which means every letter is a vertex of a square:

If you’ve ever tried to construct a crossword, you’ll find that the framing of a crossword grid under square theory feels right. When you’re nearing the end of the grid-filling process, finding valid crossings of words to fill that final corner of a grid, there’s a satisfying “clicking” feeling—a sense of magic—when it all fits together, analogous to the wrapping-around feeling of completing the square.

Taking a step back, that means the clues, the themes, and the very grids of crosswords all share the same abstract fundamental structure, the square:

If you accept the premise that squares are satisfying, square theory offers a unified theory for why crosswords are satisfying too. And if squares are fundamentally compelling, the crossword, in its recursively square structure, starts to look like an equally fundamental art form. Like if you started an English-speaking civilization from scratch, someone, somewhere would inevitably reinvent the crossword. And then someone would start a crossword Discord server, and maybe they’d call it Crosscord.

It’s hip to be square

If you’ve read this far, I promise you’ll start to notice squares popping up all over the place in your daily life. I can attest, because I’ve been honing the concept for this post for about two years now, and I often find myself thinking “that’s a square!” whenever I come across a tight joke or title or crossword theme.

If you’re a creative person, square theory is a useful framework to keep in mind. If you’re coming up with a title for a paper or a brand name, try to see if you can think of one that completes the square. If you’re writing puns for a popsicle stick or a Laffy Taffy wrapper, you can use squares to model your setups and punchlines. If you’re constructing a crossword, consider whether your theme or your question mark clues can form squares.

And if you’re writing a story or a news article or a blog post, there’s fundamental value in making it come full circle, or perhaps full square.